First published by Bob Sapatkin on Philly.com : http://bit.ly/2jvz49j

With a looming Tuesday deadline to sign up for insurance subsidized under the Affordable Care Act this year, consumers face all the usual fine-print complexities, plus new questions raised by the repeal-and-replace tumult in Washington. Chief among them: Will my health coverage – or the subsidy that makes it affordable — disappear? Probably not, experts say, because the law’s complexity and the potential chaos of such a sudden change will likely delay legislation, even as President Trump took actions last week that could slow last-minute enrollment. Another: Will my doctors be in my plan? Probably so. In the Philadelphia region, it turns out that insurers offer consumers an unusual amount of choice.

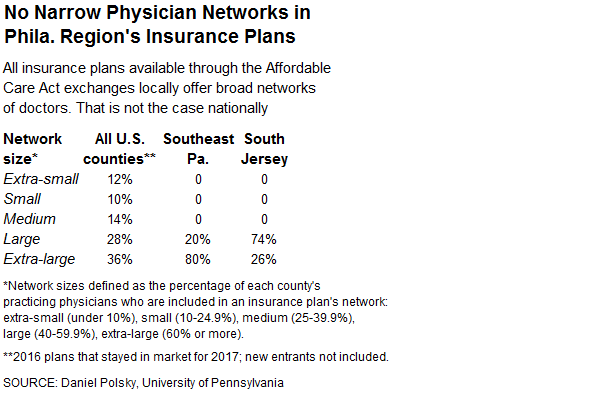

Insurance plans in both Southeastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey have some of the broadest physician networks in the United States, according to data analyzed for the Inquirer by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics.

Not a single plan available through the ACA marketplaces this year in either area includes networks that they considered narrow, compared with 22 percent of plans nationwide. None were medium-size, either; 100 percent of local plans were “large” or “extra-large.”

Although the Penn economists studied only ACA plans on the non-group market, insurers tend to use the same networks over multiple plans. So the pattern is likely similar for many employer-provided policies, which are far more common.

As controversial as it has been, the Affordable Care Act revolutionized how health insurance is purchased. Consistent standards and requirements allowed plans to be compared, apples to apples, for the first time. On the HealthCare.gov website, which long ago overcame the problems of its launch, consumers can view multiple plans’ projected costs and benefits, adjusted for how much individuals intend to use the insurance.

What the site cannot do (except in four states with pilot projects), however, is provide a clue about network sizes. And while the ACA requires that insurers post and regularly update lists of doctors who accept the coverage, the lists are notoriously inaccurate.

Plus, there are “big problems with balance billing” when patients find they must go outside their networks for care, said Timothy Jost, an emeritus professor at Washington and Lee School of Law who studies health policy.

Penn’s Leonard Davis Institute for Health Economics has been studying ACA data since the subsidized marketplace opened in 2014, with a special project devoted to network size. In his analysis for the Inquirer of plans currently available for purchase, institute executive director Daniel Polsky, a professor at the medical and Wharton schools, used data collected by New York-based health-care services company Varicred Inc. for every county in the nation.

His team found that large physician networks were more common last year on both sides of the Delaware River than in most metro areas or the nation as a whole. In Southeastern Pennsylvania, the pattern grew even stronger for 2017 because every insurer with a smaller network dropped out of the market.

But the dropouts also were partly responsible for the unusually large increase in the unsubsidized price of the average plan: Many of the narrow-network offerings had been cheaper. (Subsidies rise along with premiums, so most purchasers pay the same amount.)

Insurance markets regulated by Harrisburg and Trenton are quite different — New Jersey, for example, banned discrimination based on preexisting conditions long before the ACA, making policies more expensive. So what explains their shared outlier status when it comes to physician networks?

There are several possibilities:

- “One thing both regions have in common is that they are dominated by the Blues,” said Linda Schwimmer, president and CEO of the New Jersey Health Care Quality Institute. Independence Blue Cross in Philadelphia and Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield in South Jersey both belong to the nonprofit federation that “historically had broader networks,” she said, as a result of both philosophy and business imperatives, since the national association grants franchises that are geographically limited. They don’t have the flexibility to move into — or out of — markets based on local conditions in the way that Aetna or UnitedHealthcare can, she said.

- Another possibility is tiers. Like shrinking the size of a network, creating tiers — you face a higher co-pay and, often, deductible for physicians in a higher tier — is one of the few cost-saving options available to insurers who can no longer control spending by reducing certain benefits or rejecting applicants with preexisting conditions.

More than 20 percent of ACA plans in this region include tiers, compared with about 2 percent nationally, according to the Penn data.

- Geography may play a role, at least in New Jersey. Historically, employers have had workers commute from every corner of the state, Schwimmer said, so they wanted broad networks.

Consumer preferences when weighing insurance plans also have been evolving away from price and toward having a wider choice of doctors.

“The last couple of years, consumers said that their satisfaction is lower for narrower networks,” said Erica Hutchins Coe, an expert on health-care reform at McKinsey. Still, the management consulting company’s annual survey found that ongoing subscribers who did switch plans were more likely to leave broader networks in favor of narrower networks that were cheaper, she said.

That option is no longer available in the Philadelphia region, where all the networks are broad and ACA plans’ prices before subsidies are higher than the national average.

The average premium price for a nonsmoking 50-year-old buying the benchmark second-lowest silver plan is $584 a month in Southeastern Pennsylvania and $473 a month in New Jersey, according to an analysis of federal data by Avalere Health and the Associated Press. Nearly 80 percent of purchasers receive subsidies based on income, however, and some pay nothing at all.

“I think there is opportunity for new entrants to come in with narrow network plans,” said Penn’s Polsky.

That comment referred to future years. Despite Republicans’ promises to immediately repeal the ACA, policy experts generally believe that the insurance will not disappear this year. If it did, marketplace policyholders — more than 12 million have signed up so far through federal and state exchanges —would lose their coverage (20 million if Medicaid expansion ends, as well).

Despite the political turmoil, more than 413,000 Pennsylvania residents had chosen plans, and 277,000 in New Jersey, in the last update issued by the Obama administration.

But the Trump administration on Thursday acted to slow an anticipated final surge in enrollment by cutting outreach and advertising, although the sign-up website appeared to be working.

Last-minute purchasers tend to be younger people, who often are healthier, and therefore coveted by insurers.

Pulling the ads is “another blow to insurance companies who will have underpriced their products because they priced them without anticipating Trump policies,” Polsky said Friday. “The likelihood of this happening has certainly risen as a result of this Trump maneuver, but there are just too many variables for any potential beneficiary to factor this into a decision to enroll or not.”

The deadline is Tuesday. “There is no reason not to enroll,” Polsky said.